By Kris Leonhardt

Editor-in -chief

Continued from last week

After the construction of Fort Howard on the west side of the Fox River, the country started getting a hold on the fur trade.

In Col. Ebenezer Child’s recollection of the area, preserved in Wisconsin Historical Collections Vol. 4, he states, “In the winter of 1820, the (U.S.) President sent out a commissioner to examine the land claims of the French settlers at Green Bay. Under the ancient French regime, they had guaranteed to them as much land as they could cultivate. In examining these claims, it was found that while they varied in extent, they were very narrow on the river, running back three miles. The next spring, the President sent out patents for these claims.

“The inhabitants of the settlement, exclusive of the [Native Americans], were mostly Canadian French, and those of mixed blood. There were, in 1824, at Green Bay, six or eight resident American families, and the families of officers stationed at Fort Howard, in number about the same,” Childs stated.

Area surveyor, Albert G. Ellis, calls the existence of the old cemetery at that time.

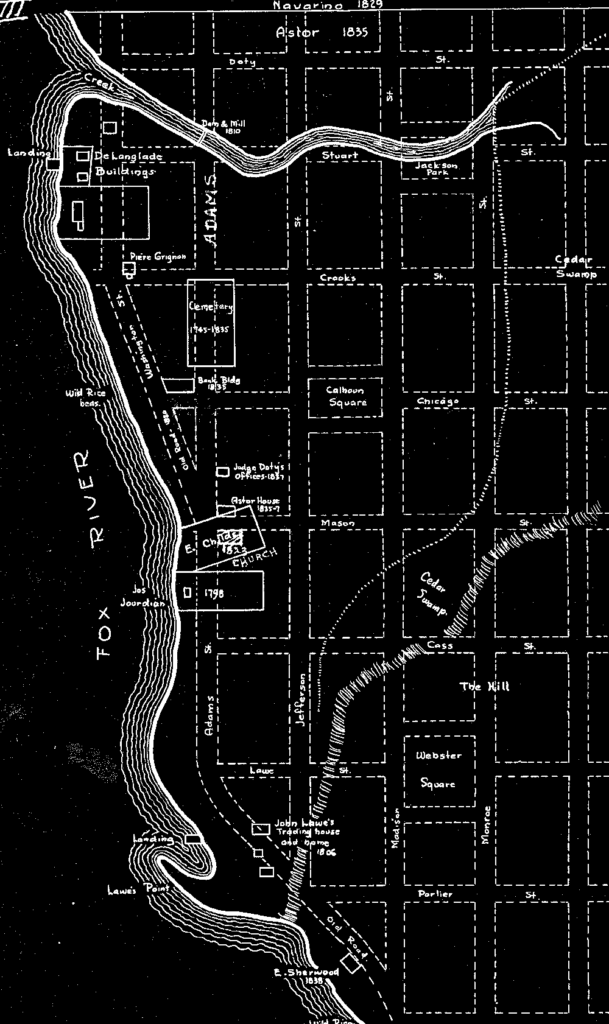

“Just above this house of Pierre Grignon, Jr., was the cemetery, picketed in and under the control of the Catholics,” Ellis stated.

“This old cemetery was used as a burial place by the French and English traders and habitants of La Baye for more than a century. Most of the noted men of Green Bay who died between 1720 and 1835 were buried here.”

Augustin Grignon also mentions the cemetery in his recollections, contained in Wisconsin Historical Collections Vol. 7, saying that internments continued until the village of Astor was platted there.

Behind the American soldiers came the American traders, as the fur trade continued as the principal industry until about 1830.

In 1835, a land office was opened in Green Bay

“At the first sale of lands at Green Bay, there was a great rush to purchase, mostly from Milwaukee and Chicago,” Childs recalled.

The village of Astor was platted in 1835 on land that had been seized by the American Fur Company and incorporated by New York mogul John Jacob Astor, and buildings began rising out of the sandy hill.

As the property surrounding the cemetery location was built upon, bodies were removed to the Catholic cemetery in Allouez.

Mrs. Henry S. Baird, in a July 1882 edition of the Green Bay Weekly Gazette, recalled that a small Roman Catholic Chapel once stood on the north side of Chicago Street between Adams and Washington

“where later the old ‘Bank Building’ was placed, and east of this was the graveyard, taking in about a square,” she stated. “Graves were at one time underlying what is now Adams Street.”

The October 1886 edition of the Green Bay Press-Gazette later chronicles the discovery of human remains at this location while construction work was being completed.

“This forenoon the workmen employed in digging the water trenches on Adams Street near the old bank building discovered, in nearly perfect condition, several human skeletons about a foot below the surface which, as soon as exposed to the action of the atmosphere, fell into pieces at the slightest touch. Within the distance of a few rods six skeletons were found, together with the mouldering remains of decayed coffins,” it read.

The article stated that there was no record that “there was any formal or general attempt to remove remains anywhere” at the time the land was redeveloped and that it was “probably most of the original burials remained undisturbed.

“Old residents recall the fact that immediately succeeding the laying of the street through the enclosure, passing vehicles would uncover and throw up the bones from their shallow resting place.”

Continued next week