By Rick Cohler

Contributing Writer

GREEN BAY – Brown County Circuit Court District Judge Donald Zuidmulder served as Brown County district attorney from 1971-75 then he returned to private practice until 1997 when he was elected to the judiciary.

“When I became a judge six or seven years later, it dawned on me that while the traditional criminal justice system does have a deterrent effect on some people, the reality is that others seem to cycle all the way through the system and they come out of prison and re-offend.” Zuidmulder said.

“It occurred to me that the traditional justice system doesn’t make an impact on these people. I did some soul searching and research and found that there is a judge in Florida who came to the conclusion that 80% of the people in the system have mental health or substance abuse issues so he decided to focus on that group of non-violent offenders and whose offenses revolved around substance abuse. Then he created a court that focused on getting them treatment for the engine that drove the criminal behavior and he had considerable success.”

The treatment courts have a recidivism rate of 38% five years after a participant completes the program compared to 65% for others who have not been in the treatment courts.

After getting support from then Brown County Executive Tom Hinz, Zuidmulder went before the County Board.

“I said all the judges are full-time state employees and we have have full calendars but this is something I’m willing to volunteer to create because it is the right thing to do for the community,” he recalled.

The Board approved funding for the court in March 2008 and it held its first session on July 31, 2009.

Current County Executive Troy Streckenbach is also a strong supporter of the alternative courts. “In the end they’re a human being, they’re in many cases a productive member of society with families,” Streckenbach said. “The judges were finding that the behavior that landed them in front of a judge was due to an addiction; something that could be corrected if handled.

“This isn’t for everyone. It’s very clear that people who belong in jail belong in jail. They go to prison based on their offenses.

“If we’re able to allow people to have a second chance, be monitored by the courts, tested on a daily basis, the full-on regimen, it can make a real difference. They’re held accountable so this is not a pass to go back out and re-offend.”

The treatment courts are also cost-effective, Streckenbach said.

The program’s Day Report Center provides testing and manages accountability for 75-125 offenders for an annual cost of $350,000 compared to $12-14 million to construct a new jail pod and $700,000 to fund it annually. The alternative courts have had total expenditures of $7.06 million, since 2009 with $3.8 million of that coming from the tax levy.

The treatment courts utilize the county’s PALS program to work with children in troubled families.

Volunteer mentors spend time two to three times per month in a recreational or learning activity with a child, age three or older, who has been referred by Brown County Child Protective Services.

Volunteer mentors help the child adjust to the separation or loss of a parent, enhance self-esteem and confidence, and learn new skills.

The goal is to prevent the majority of these kids from ending up in the juvenile justice system, then in the adult criminal justice system.

“Somewhere, somehow we have to break the generational cycle because the adult that was before him with a behavioral issue driven by an addiction started early on because of some form of trauma,” Strechenbach said, pointing out that 83% of the children in the juvenile justice system have had earlier contact with child protective services.

“I firmly believe if we, as a society, are going to change the social inequities, the disproportionate representation, or just the amount of people going into our prison system we have to start with the kids.”

The Alternative Courts program is trying to address the adult behavior that didn’t get managed at an earlier point in time.

“Hopefully we can correct it and help this individual regain their family and be a productive citizen of our community. At the same time, we’re trying to get the community to wrap their arms around these kids so they don’t repeat what they’ve learned in their home or their neighborhood. It’s about giving the individual an opportunity to correct a behavior, regain custody and access to their children and their families and hopefully not have their children repeat. This is not to be soft on crime; this is us being Christians and humanitarians and believing if our neighbor falls we’re going to help him get back up. But at the same time if they’re doing something wrong and they’ve committed a serious crime, they need to go. This is not being soft on crime this is being smart on crime,” Strechenbach said.

“If we have 5,200 call-ins for Child Protective Services and 1,800 of those are screened in, basically I’m building a jail in six years for those 1,800 which amounts to $14 million and $700,000 in taxes to pay for the management of that child; who at that point in time didn’t know it was going to live out the crime of that experience. It happened because they didn’t manage the trauma in the home; that’s what we have to disrupt in our country if we’re going to change the way things are going.”

Overall, the program has proved successful.

“Our family recovery court has 41 kids in that program and if we’re successful we’ll have 41 kids that aren’t going to have drug use in their houses, aren’t going to have parents who are in and out of jail, they’re going to have a support system with two loving parents,” he said.

Violent offenders, those who used firearms or dangerous weapons in crimes, sexually based offenders, or enterprise drug dealers (dealers who use proceeds for their lifestyle, housing, their cars, or other lifestyles) are not eligible, according to Mark VandenHoogen, the Criminal Justice Services manager for Brown County Health and Human Services.

“The ones we want to target have been using drugs and are in the system and consuming a lot of money,” VandenHoogen said. “If you take the drugs away and manage the mental health symptoms, they can become part of the community.

“Before the treatment courts, the 290-bed work release center was full and we were sending people to other counties. Now it’s empty: we’re not using it. You’re not seeing these people committing crimes; you seeing them become members of the community.”

A person can be referred to the alternative courts after their conviction by officials, family or others.

When the referral is made, the Brown County district attorney’s office does a thorough examination of person’s past.

Some of the charges on the initial examination may not be enough to deny the application, according to VandenHoogen.

“You may have the charges in front of you right now that are on the edge of what you feel comfortable with but then you have to start using some additional factors,” he explained. “I think our DA’s office does a good job of factoring those in because at the end of the day there are clear-cut items that you can or can’t deny for so they’ll pass them on through but say they don’t support this at the triage level which I think is fair. It’s my job as the leader of the treatment team it’s my responsibility to understand those limitations to help the person through that process. The criminal justice system is messy. If you have someone with addiction or mental health issues and expect them to go through all the different appointments it’s very challenging for someone who doesn’t have a lot of support.”

An applicant is put through the Risk and Needs Triage (RANT) tool which yields an immediate and easily understandable report that classifies offenders into one of four risk/needs quadrants, each with different implications for selecting suitable correctional decisions by judges, probation and parole officers, attorneys, and other decision-makers.

The risk to repeat determines the level of intervention needed.

“It’s a sweet spot,” VandenHoogen said. “Too much treatment and too much oversight may make someone worse and not enough can make them worse too. We’re talking about the criminal-thinking population that their initial thought is if they’re asked if they think something bad is going to happen because of their behavior they say no because if they say yes they’re going to get in trouble for it.”

A deep bio-psycho-social exam which provides a deep dive of their life events is also conducted using the Texas Christian University drug scale or TCU-5 to determine the severity of use and a mental health screening is used to locate any underlying mental health disorders.

A case worker is then assigned who makes several visits to the participant each week and the participant is required to appear before the judge of their court each week.

Failure to comply with all of the requirements results in being returned to a jail cell for a period of time as a consequence.

At a recent court session, one participant was remanded to the jail for a weekend for not completing his testing and having a nonchalant response to his caseworker’s questions.

Since 2009, about 190 people have been in the drug court.

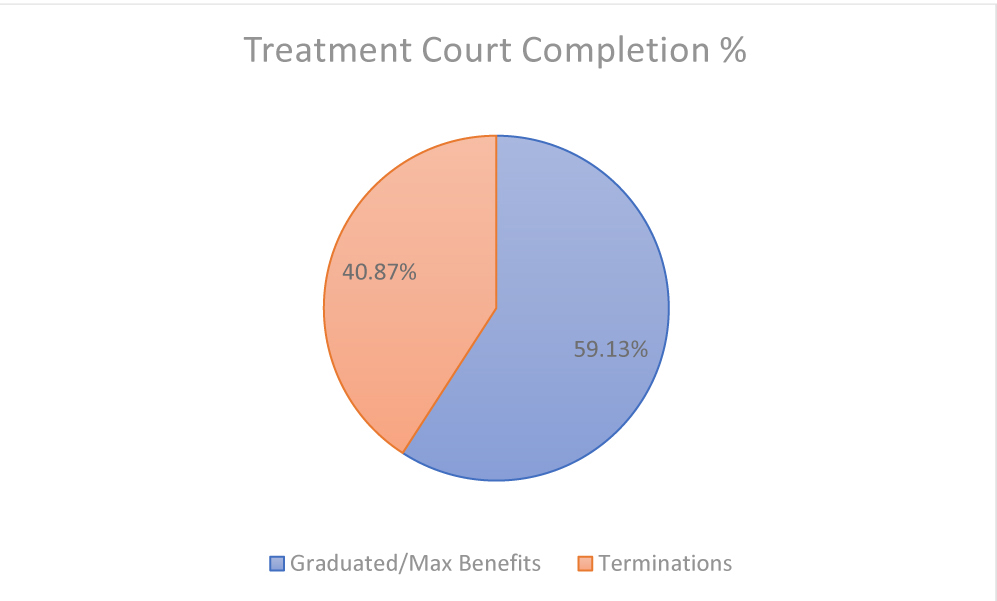

The treatment courts, as a whole, have a completion rate of 59%.

Note: Brown County operates five alternative treatment courts: Drug Court, Veterans Court, Mental Health Court, Heroin/opioid Court and OWI Court. Over the coming months, the Press-Times will detail the workings of these alternative courts.