By Kevin Damask

Correspondent

GREEN BAY – Momentum continues to build in the Green Bay area for the National Estuarine Research Reserve (NERR), a federal designation to help protect and study coastal wetlands and natural estuaries.

Emily Tyner, the director of freshwater strategy at University of Wisconsin-Green Bay (UWGB), was pleased to see a large turnout, both virtually and in-person, during two public site selection meetings Sept. 7-8 at UWGB.

More than 140 people attended, and Tyner was still taking submitted written comments through Sept. 15.

“No one spoke against it, which was good,” Tyner said. “Most of the comments were that people wanted to see more land included in the sites being considered. We understand that as people have their favorite spots. We’ll definitely consider that going forward.”

The bay of Green Bay is the world’s largest freshwater estuary, according to UWGB.

Land set aside for the reserve is designated through a six-step process that usually takes about four to six years to finish.

UWGB hopes to complete the process by early 2025.

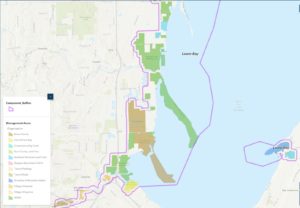

Currently in step two, the Green Bay NERR is evaluating potential site locations with plans to designate about 11,500 acres of public property along the east and west shores of Green Bay for the reserve.

The NERR designation is non-regulatory, so no new federal rules are associated with the designation.

“There shouldn’t be any impact on fishing and hunting lands,” Tyner said, adding that no private land will be included.

A large footprint

Among the sites in the Green Bay area are city and county-owned lands along Duck Creek from Pamperin Park to the bay; west shore public lands including the Ken Euers Nature Area, Barkhausen Waterfowl Preserve and the Sensiba Wildlife Area including Long Tail Point; and east shore areas including Point au Sable and Wequiock Creek Natural area.

To the north, potential sites stretch to Door County and Michigan, including public marshlands in Peshtigo and Sturgeon Bay.

The Green Bay NERR would be the third of its kind in the Great Lakes region, joining the Old Woman Creek NERR along the Lake Erie shoreline in Ohio, and the Lake Superior NERR in Duluth-Superior.

Patrick Robinson, the UW-Madison Division of Extension dean for agriculture, natural resources and community development, worked on establishing the Lake Superior reserve, formally designated in 2010.

For the past several years, Robinson has been involved in the Green Bay project, serving on the Site Coordination Committee.

“(The bay of) Green Bay is a tremendous asset for the surrounding communities and important to the region’s quality of life,” Robinson said in an email. “A designation would result in additional funding for new employees, research and education, a visitor center, water quality monitoring and more.”

An organizing force

NERR was created through the federal Coastal Zone Management Act, a partnership through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) and several coastal states with a mission to “practice and promote stewardship of coasts and estuaries through innovative research, education, and training using a place-based system of protected areas.”

Funding for the project comes through state and federal money.

While the NOAA provides direction nationally, regionally universities or state agencies lead the project’s day-to-day guidance.

“One goal we have with NERR is it can be an organizing force to think about what the future is for water in our region, making sure the fish are healthy and people can swim, boat and recreate in these waters,” Tyner said.

UW-Green Bay is working with several wetland restoration organizations, including Ducks Unlimited-Wisconsin, to plan and build the reserve in hopes of protecting the Green Bay ecosystem for decades to come.

Climate change continues to erode the nation’s coastlines, and the damaging effects are showing along Lake Michigan coastal areas.

“Green Bay is taking an approach that’s a little above and beyond what the other NERRs do in that we look to continue some of the work they’re doing and really get into some of the applied science part of delivering coastal wetland conservation, especially in an important area like Green Bay,” Brian Glenzinski, regional biologist, Ducks Unlimited – Wisconsin, said. “Working with UWGB and the NERR should help us deliver better conservation in the long run.”

National visitor center

The NERR designation includes funds for construction of a visitor center somewhere in the area, which stretches as far north as Marinette and the islands off the tip of Door County.

Several communities, including Sturgeon Bay, are already working on their bids to host the visitor center.

“Per guidance by NOAA and our own guidance, we certainly don’t want to identify a location for a visitor center until we have the boundaries for the natural areas,” Tyner said.

Since the project uses federal and state funds, budget constraints limit the size of the reserve.

Tyner said the Green Bay reserve aims to be the 33rd or 32nd largest NERR in the U.S.

One of the program’s key goals is to teach K-12 students the importance of natural waterways, how erosion can hurt the ecosystem and ways to safeguard local coastlines from additional damage.

“The program at its footprint is not only for all of Northeast Wisconsin, but is designed to serve all of the Lake Michigan-Lake Huron shoreline,” Tyner said. “That means access to teaching resources and schools or working with non-profit groups and communities along the lakeshore that’s not bound by the reserve. The idea is to serve a lot of people.”

Having seen the Lake Superior NERR develop from an idea to reality, Robinson knows how much collaboration is needed to make the Green Bay NERR successful.

“The most challenging and rewarding aspects are completing the intentional work of building and strengthening collaborations and subsequently completing the work within the project timeline,” Robinson said.

The years of planning, securing funds and long hours spent developing the NERR will be worth it, Robinson said.

“I truly believe this is a fantastic opportunity that will pay dividends for the residents and communities of the region for decades to come. I feel very fortunate to be part of the process.”

A group effort

For Ducks Unlimited, the opportunity to expand work it was already doing to restore the Green Bay wetlands with help from UWGB and NOAA was a no-brainer, Glenzinski said.

“Science has pointed us to this place because it is a special place,” he said. “It once supported huge amounts of waterfowl. We’ve got the challenges from habitat degradation from years of abuse on the Fox River and elsewhere in that area that have impacted what was a very productive area, but that also gives us a ton of potential to work with and restore those habitats that were lost.”

With support from the Wisconsin DNR and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, other groups realized the benefits of building a reserve, including Green Bay Duck Hunters and the Northeast Wisconsin Land Trust.

“It really is pretty impressive up in that neck of the woods,” Glenzinski said. “There’s a bunch of partners in the conservation community that will really benefit from the NERR and it will really be an awesome opportunity to pull the NERR into an impressive program that’s already working up there.”