By Kris Leonhardt

Editor-in-chief

Continued from previous week

The 1909 “White House Conference on the Care of Dependent Children” initiated by President Theodore Roosevelt brought together social workers, educators, juvenile court judges and other civic leaders in opposition to the institutionalization of neglected and orphaned children.

The conference led to the creation of the Children’s Bureau, the widows’ pension movement and the growth of adoption agencies.

“At the 1930 White House Conference on Child Health and Protection, Home Folks, a long-time critic of orphanages, reported that 220,000 needy children remained in ‘their own homes,’ thanks to state mother’s pensions; these allowed women to care for their children at home rather than place them in orphanages. At long last, Folks hoped, professional social workers were able to implement the ‘fundamental principles of social work’ articulated at the 1909 White House Conference on Dependent Children: most significantly, ‘home life is the highest and finest product of civilization….Except in unusual circumstances, the home should not be broken up for reasons of poverty.’ But the nation had already descended into the Great Depression, an ‘unusual circumstance’ that devastated families and moved thousands of children into foster homes and orphanages,” wrote Marian J. Morton in “Surviving the Great Depression” for John Carroll University.

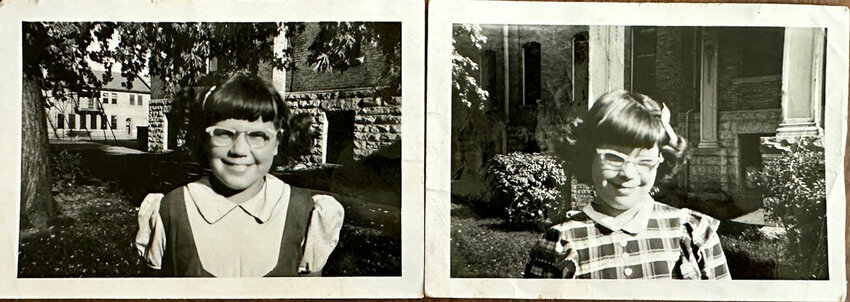

One of those children affected by “unusual circumstances” was June Muller, now 91 and living in the Green Bay area.

“I was about 12 years old when my sister and I were placed in the orphanage because my mother couldn’t take care of us and nobody else in their family,” recalled Muller, whose father had died young from cancer.

Muller and her sister, JoAnn, were born in Illinois, but after their dad’s passing, their mother moved them to Wisconsin where she hoped that the girls’ grandmother could assist.

“And she couldn’t take care of us; so, she put us in the orphanage to have a place to keep until she could find a job and an apartment,” Muller added.

Muller and her sister were placed at the St. Joseph’s Orphanage.

“We were away from our mother and we were kept being told that my mother was coming to get us,” Muller said.

“We had to put up with the rules and regulations; it was run by nuns and priests.

“There were a lot of other kids that were running away that had no place to go that were also placed in the orphanage.

“We all had chores to do, and we all had like serial numbers in our clothes so they knew who we were, and we all went to church every day.

“The orphanage wasn’t the sweetest place to be, believe me. It was the place that took care of us, taught us things; we went to school there.

“We were all there for different reasons.”

Even after a year, when their mother was back on her feet she still needed to prove her stability before the girls were returned to her custody.

“My mother worked hard to win us back,” Muller added.

Bea Seidl recalled a cold day in 1942 as she was deposited at the St. Joseph’s Orphanage with no explanation as to why her mother lost custody of her and her siblings.

“Sister Edythe closed the door, pulled the chair to the room’s center and snapped her fingers at me, indicating I was to sit down. I thought otherwise and almost made it to the door before the nun caught me by the arm and forced me into the chair. Producing a pair of scissors, she cut my hair with no thought to any style. It fell to the floor in ragged bunches,” she recalled in her book Orphan Doors.

“Sister Edythe undressed me and tossed my new dress and shoes away as if they were rags. Before I could object, the nun motioned me into a shower where she proceeded to scrub me from head to toes.

“Out of the shower, I sneezed as she raked a powdery substance through what remained of my hair.”

Seidl spent eight years with what is described as stern nuns, rigid regimens and scant tenderness.

But as more and more national reform was instituted and the Depression subsided, the number of institutionalized children declined.

Continued in next week’s edition